- Over 1.4 million Americans have tired meth this year.

(source: 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health)

- Over 12.3 million Americans age 12 and older have tired meth since 2003.

- Meth use is greatest among 35-45 year olds.

- The biggest increase in treatment is among 18-25 year olds.

- Meth treatment admission has outpaced cocaine and herion in 14 US states.

- "Ice" currently sells for $12,000 to $16,000 per pound at the wholesale level.

(source: A&E documentary "Meth in the City" aired 12/17/06)

According to the Oregonian newspaper in November 2006:

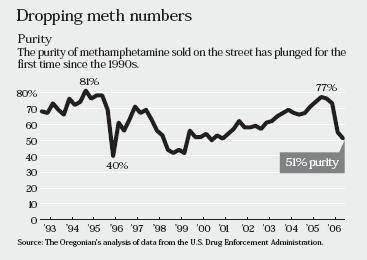

The purity of methamphetamine has fallen sharply across the country while its price has increased, suggesting that a crackdown on meth ingredients in Mexico and the United States has dramatically curtailed production of the drug.

Meth seized by drug agents in spring 2006 averaged 51 percent pure, down from 77 percent in spring 2005, according to The Oregonian's analysis of federal data. At the same time, prices have more than doubled. A gram of uncut meth cost about $260 this past spring, up from $100 a year before. It was the first significant, sustained decline in purity and increase in price since 1997.

The impact on meth use nationwide cannot yet be calculated. But some treatment providers and meth users in Oregon say people are using meth less frequently and not getting as high when they do. Studies have shown that fewer people use drugs when purity is low and the price is high. Rob Bovett, legal counsel to the Oregon Narcotics Enforcement Association and a national meth activist, said the drop in purity signifies progress against meth producers. "What's happening is clear as day," Bovett said. "They're making less meth."

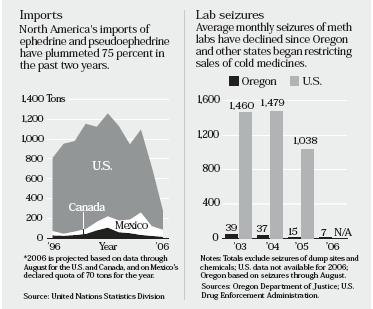

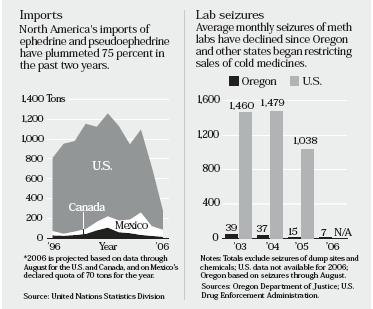

The setback for the meth trade follows tight restrictions by the United States and Mexico on ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, ingredients in cold medicine that are used to make meth. Starting in 2004, dozens of states began requiring an ID and signature to buy cold remedies with pseudoephedrine. Drug companies responded by introducing cold remedies with phenylephrine, which won't make meth. Seizures of meth labs fell by 59 percent in Oregon and 30 percent nationally from 2004 to 2005. U.S. officials predict further reductions because cold-pill restrictions became law nationwide on Sept. 30.

South of the border, Mexican officials took a more direct approach. They slapped stringent quotas on companies that import pseudoephedrine. They barred middlemen from the business and shut down suspicious pharmacies. The results for the chemical and pharmaceutical industries are staggering. North America's imports of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine, trade data show, have declined 75 percent since 2004. The projected 850-ton reduction equals half of global trade in the chemicals for 2004, statistics from the International Narcotics Control Board show.

Ephedrine and pseudoephedrine manufacturers overseas have suffered devastating losses in sales. Now there are signs that the reduction in imports also is contributing to a violent struggle among Mexican traffickers, who supply an estimated 80 percent of meth that Americans consume. On July 24, robbers stole 1 ton of pseudoephedrine from a pharmaceutical company warehouse in Mexico City. The thieves left behind four security guards bound, gagged and stabbed to death. The degree of violence was unprecedented for a pseudoephedrine heist. But the motive was powerful: A 25-kilogram barrel of pseudoephedrine, worth $1,500 in the legitimate marketplace, reportedly costs $220,000 on the Mexican black market.

Mexico's top prosecutor for organized crime, Jose Luis Santiago Vasconcelos, said the sharp drop in imports has made traffickers desperate to acquire pseudoephedrine. "That reduction is the crisis that we see here today," he said. U.S. and Mexican officials are coordinating efforts to curb diversion of meth's essential ingredients.

Christy McCampbell, the State Department's new deputy assistant secretary for counternarcotics, said her first official visit to Mexico focused primarily on meth because of the country's booming production of the drug in recent years. "They've been cooking, cooking, cooking down there," said McCampbell, who learned about meth superlabs as head of California's Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement. But McCampbell said Mexican officials are ready to attack the meth problem. "They are becoming acutely aware of it," McCampbell said, "and they've made every indication that I can see that they want to work with it."

The profound shift in the meth world has been hard to miss, according to police, treatment counselors and users. Oregon State Police Detective John Mogle, a member of the Klamath County Interagency Narcotics Task Force, said dealers increasingly dilute or "step on" their meth with additives. "If you get down to the small user that's buying the eight ball, your percentage is going to be way low, because it's been stepped on so much," Mogle said, using the street term for one-eighth of an ounce. "I think everywhere, the whole state's seeing that."

Mogle said a pound of meth in Klamath County went for $6,000 in early 2005; now it's $11,000 to $13,000. Ounces last year ranged in price from $500 to $600; now they sell for $1,100 to $1,200. Although it is too soon to quantify how meth users are responding to weaker, more expensive meth, there are promising signs. "What we're hearing from clients is that the meth that is around has probably been cut more, and they're not getting as high from it," said Rita Sullivan, executive director of the OnTrack treatment program in Medford. What's more, the drug is hard to come by. Kelli Bradley, 33, of Medford stopped using meth in July 2005 after joining a recovery group. When she relapsed eight months later, she no longer could get as high as she wanted, anytime she wanted.